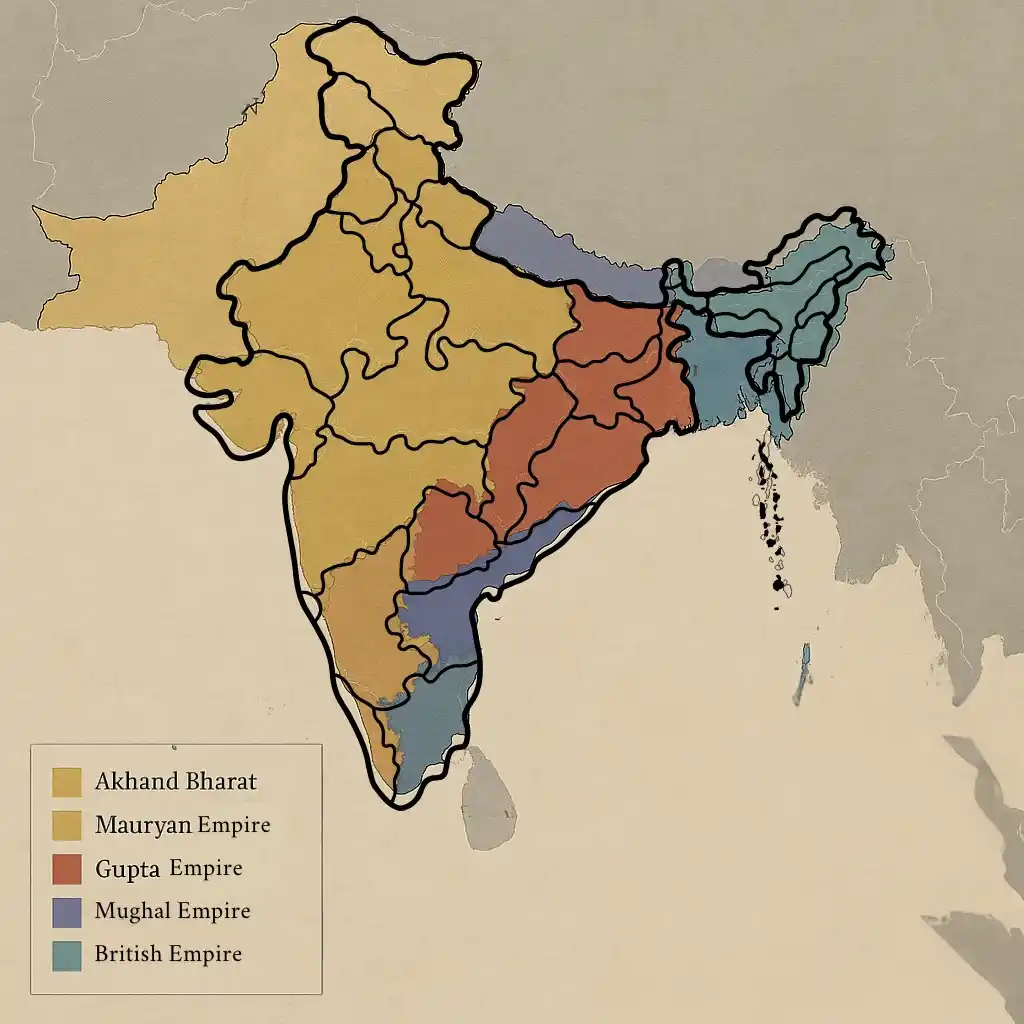

India’s economic journey is deeply intertwined with its rich and complex history, shaped by successive empires, shifting trade dynamics, and evolving administrative systems. To fully grasp the trajectory of the Indian economy—from ancient prosperity to colonial restructuring and post-independence development—it is essential to understand the territorial context within which these changes unfolded. Each era not only brought new economic policies and priorities but also redefined the physical boundaries of the Indian subcontinent. The following map serves as a visual introduction to this historical backdrop, illustrating the extent of Indian territory during key periods in its economic history.

Source: Create by the author.

The map above provides a layered visual narrative of India’s territorial evolution through eight major historical eras, each reflecting significant shifts in economic structure, governance, and geopolitical influence. From the expansive vision of Akhand Bharat, representing a broad civilizational unity, to the centralized administration of the Mauryan Empire, the culturally prosperous Gupta Empire, the economically vibrant Mughal Empire, and the infrastructurally transformative British Empire, the map traces how India’s boundaries expanded and contracted over time. Each distinct shade corresponds to a specific era, highlighting the scale of Indian territory during that period. These overlapping regions visually depict the ebb and flow of India’s territorial extent, with the current Indian boundary outlined for reference. Together, the shaded layers offer a clear, aesthetic representation of how the Indian subcontinent’s geography has transformed—helping readers contextualize the nation’s historical economic journey within its shifting territorial footprint.

Getting interesting right? Check another such article: East Meets West: The Global Saga of Economic Thought

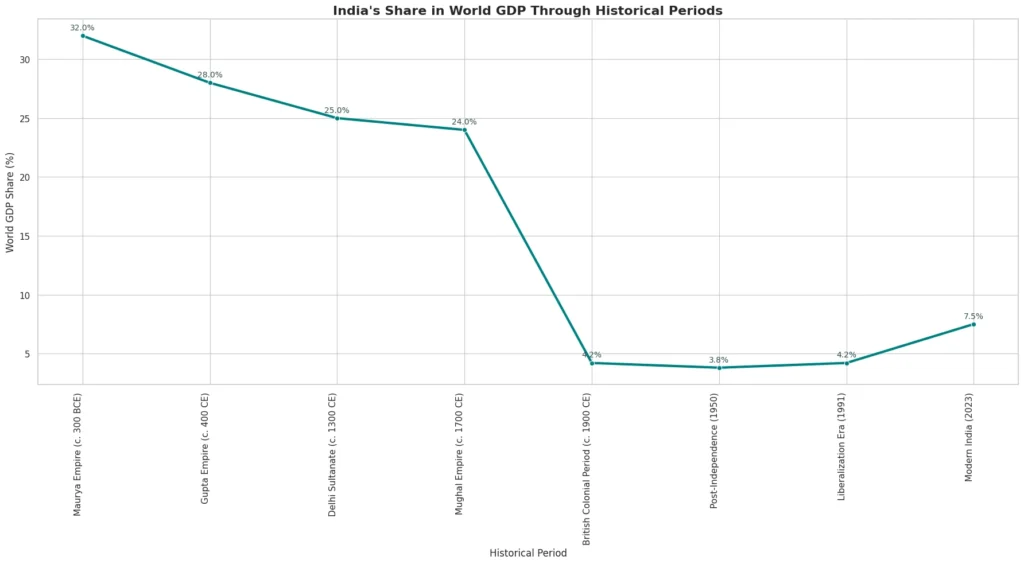

India’s economic history is not just a timeline—it is a saga of rise, disruption, resilience, and resurgence. Few civilizations in the world can boast the economic influence that ancient India once held. As the graph below illustrates, India contributed nearly one-third of the world’s GDP during the Maurya and Gupta empires, making it one of the wealthiest and most advanced economies of its time.

Source: Created by the author.

Yet, this story is not linear. Centuries of political fragmentation, invasions, and finally colonial exploitation saw India’s share plummet to just over 4% by the early 20th century. It was only after independence in 1947—and more dramatically after the liberalization reforms of 1991—that India began to reclaim its position on the world economic stage, reaching 7.5% of global GDP by 2023.

This article traces that long arc—from the conception of a united economic space under the idea of Akhand Bharat, to the rise and fall of empires, colonial rule, and the emergence of modern India. Through wars, reforms, cultural shifts, and structural transformations, we explore how India’s economic identity was shaped—and reshaped—across millennia.

1. The Idea of Akhand Bharat: A Tapestry of Micro-Economies

Long before the concept of modern nation-states, the Indian subcontinent functioned as a sprawling mosaic of civilizations unified by shared philosophical, spiritual, and cultural heritage. The earliest references to “Bharatavarsha” appear in ancient Hindu scriptures like the Vishnu Purana and Mahabharata, referring to the land that stretches from the Himalayas to the Indian Ocean. These texts didn’t define boundaries in political terms but described a region unified by dharma (moral order), trade routes, and linguistic diversity. Despite being composed of various kingdoms and tribal territories, there was a cultural cohesion that laid the foundation for the idea of Akhand Bharat.

During the 6th century BCE, the subcontinent saw the rise of 16 Mahajanapadas, each with its own economic policies, governance structures, and trade practices. These regional economies traded with each other and with foreign powers, showcasing early signs of economic interdependence. Agricultural surpluses, coinage, and rudimentary banking systems emerged, paving the way for complex economic interactions. The constant movement of scholars, monks, and merchants across these regions reinforced the idea of a connected economic space, even if politically fragmented.

📊 Fact: By 1 CE, India accounted for 32% of the world’s GDP (as per Angus Maddison), thanks to thriving agriculture, metallurgy, textiles, and international trade networks.

2. The Mauryan Economic Order (321–185 BCE)

The Mauryan Empire, founded by Chandragupta Maurya with the guidance of Chanakya, was the first political unification of the Indian subcontinent. Its capital, Pataliputra, became a hub of administrative and economic innovation. The Arthashastra, written by Chanakya, outlined economic policies, including state control of trade, regulation of markets, and taxation methods. Land revenue formed the backbone of the economy, and infrastructure such as roads, granaries, and irrigation systems was state-funded to support agrarian expansion and trade.

Emperor Ashoka, the most celebrated Mauryan ruler, transformed the empire’s economic policy through his embrace of Buddhism and ethical governance. He emphasized welfare economics, building hospitals, rest houses, and roads. Trade routes such as the Uttarapatha and Dakshinapatha facilitated the movement of goods like spices, gemstones, and textiles. The empire maintained a standing army and civil services, funded through taxes on agriculture, trade, and crafts. The Mauryan economy was a blend of centralized planning and regulated free enterprise, laying early foundations of a welfare state.

🧱 Visualize Ashoka’s empire as a network of arterial trade routes where merchants, monks, and migrants exchanged goods and ideas across thousands of kilometers.

3. The Gupta Golden Age (320–550 CE)

The Gupta Empire ushered in a golden age characterized by economic prosperity, scientific innovation, and artistic excellence. Unlike the more centralized Mauryan state, the Gupta administration was more decentralized, relying on local guilds and feudal landholders for governance. These guilds (shrenis) were pivotal to urban economic life, regulating production quality, prices, and labor practices. Artisans, weavers, and metalworkers flourished under their patronage. Gupta-era coins bearing inscriptions of rulers and deities indicate robust commerce and monetary policy.

India became an essential node in the Silk Road network during this period. The export of muslin, silk, spices, and ivory to Rome, China, and Southeast Asia brought immense wealth. Education centers like Nalanda attracted foreign students, contributing to economic as well as intellectual trade. Temples often doubled as banks and warehouses, and land grants to Brahmins and monasteries created agrarian surpluses. The prosperity allowed for advances in mathematics, astronomy, and medicine, which in turn supported the economy through practical applications in agriculture and architecture.

📊 By 500 CE, India’s GDP share stood around 28% of the global economy (Maddison), demonstrating a stable and productive economic structure.

4. Medieval Shifts: From Sultanates to the Mughals (1206–1707)

The decline of classical Indian empires gave rise to a series of Islamic Sultanates and regional Hindu kingdoms. The Delhi Sultanate introduced new administrative practices like the Iqta system, which redistributed land revenue to nobles and military officers. Urban centers like Delhi, Multan, and Lahore became bustling trade hubs. The introduction of Persian coinage, new crops (like citrus and rice varieties), and irrigation techniques contributed to the transformation of the agrarian economy. The social structure began to change with the rise of a merchant class and the increased participation of Muslims in trade and crafts.

The Mughal Empire, especially under rulers like Akbar, Jahangir, and Aurangzeb, elevated the economy to new heights. Akbar’s land revenue system (Zabt) was based on detailed crop surveys and set revenue rates accordingly. The empire invested in roads, caravanserais, and markets, supporting internal and international trade. Indian textiles, particularly from Bengal, were in global demand. Shipbuilding and port cities like Surat and Masulipatnam facilitated maritime trade. Despite its agrarian backbone, the Mughal economy demonstrated early features of proto-industrialization with a significant artisan population.

📈 The Mughal empire contributed to a rich agrarian economy, with over 15% of world manufacturing output coming from India.

📊 By 1700, India still held 24% of world GDP.

5. Colonial Extraction (1757–1947): The Great Economic Drain

The colonial era began with the Battle of Plassey in 1757, allowing the British East India Company to establish control over Bengal’s rich revenues. This marked the beginning of a systemic extraction economy. Indian industries, especially handloom textiles, were deliberately destroyed through high tariffs and discriminatory trade policies, converting India into a raw material supplier. The Drain Theory, proposed by Dadabhai Naoroji, explained how wealth was siphoned off to Britain through unfair trade, dividends to British investors, and the cost of British administration.

Colonial policies prioritized cash crops like indigo, tea, and cotton, which led to food shortages and frequent famines. Infrastructure like railways and telegraphs were built, but mainly to serve British military and commercial interests. While some industrialization did occur, such as in jute and steel, it was stifled by lack of investment and autonomy. By the time of independence, India was one of the poorest nations in the world despite once being one of the richest.

📉 India’s GDP share shrank from 24% in 1700 to just 4.2% by 1950.

6. Post-Independence Socialist Economy (1947–1991)

Upon independence, India faced enormous economic challenges—partition-induced displacement, food shortages, and an underdeveloped industrial base. Jawaharlal Nehru adopted a socialist approach inspired by the Soviet model. The Planning Commission was set up, and Five-Year Plans were launched focusing on agriculture, heavy industries, and scientific research. Large public sector enterprises (PSUs) dominated sectors like steel, coal, and energy. Nationalization of banks and insurance ensured state control over capital.

While the Green Revolution of the 1960s improved food self-sufficiency, inefficiencies and corruption plagued the license-quota-permit raj. Small-scale industries were protected but remained technologically stagnant. GDP growth hovered around 3.5%, which led to increasing disillusionment. India lagged behind Asian peers like South Korea and Taiwan, which had embraced export-led industrialization.

📊 Between 1950 and 1991, India’s GDP grew at an average of 3.5% per year.

7. Liberalization and the Rise of New India (1991–2014)

In 1991, India faced a severe balance of payments crisis with only a few weeks of foreign exchange reserves left. Under PM P.V. Narasimha Rao and Finance Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh, India initiated liberalization: dismantling license controls, reducing tariffs, devaluing the rupee, and opening up to foreign investment. These reforms spurred private sector growth, especially in IT, pharmaceuticals, and services.

Multinational companies entered the Indian market, and the middle class expanded rapidly. The rise of Bangalore, Hyderabad, and Pune as IT hubs brought employment and innovation. Telecom, banking, and retail sectors transformed. India emerged as a global outsourcing hub, and GDP growth accelerated to 6-9%. Poverty levels declined, and a new aspirational class emerged.

🧠 Think of Bangalore, transformed from a sleepy city into the “Silicon Valley of India.”

8. Modern India (2014–2024): Digital Economy and Global Presence

The last decade saw India embrace technology at scale. Under the Modi administration, initiatives like Digital India, Startup India, and Make in India aimed to modernize infrastructure and improve ease of doing business. Aadhaar enabled biometric-based public service delivery. UPI revolutionized digital payments, achieving financial inclusion at unprecedented speed. India also improved its global rankings in doing business and innovation.

India became the world’s 5th largest economy by nominal GDP. Investments in roads, ports, renewable energy, and defense manufacturing transformed its physical and economic landscape. With a median age of under 30, India has a demographic advantage that, if leveraged well, could drive growth for decades.

📊 India became the world’s 5th largest economy in 2022, with a GDP of $3.73 trillion.

📱 Over 400 million Indians use UPI monthly, with over 10 billion transactions per month in 2024.

9. What India Gained and Lost

Over millennia, India gained civilizational depth, cultural continuity, and economic resilience. It developed world-leading knowledge systems in mathematics, medicine, and metallurgy. Its democratic institutions, though imperfect, have allowed for peaceful power transitions and civil liberties. The rise of the Indian diaspora and global companies like TCS and Infosys signify India’s global presence.

However, India also suffered immense losses: destruction of indigenous industries under colonialism, millions of lives lost to famine, war, and partition, and systemic corruption and inequality post-independence. Environmental degradation, education gaps, and gender disparities remain persistent challenges. Balancing tradition with modernity continues to be a tightrope walk.

10. The Future: Bharat at 100

As India nears its 100th year of independence in 2047, the path ahead includes becoming a $10 trillion economy, achieving net-zero carbon emissions, and harnessing AI and biotechnology for development. Education reform, healthcare access, and environmental sustainability will determine whether India can provide equitable prosperity.

India’s transformation is not just economic; it is civilizational. From the idea of Akhand Bharat to a globally integrated powerhouse, India continues to evolve. The challenge lies in making this growth inclusive, sustainable, and anchored in the values that have guided it through millennia.